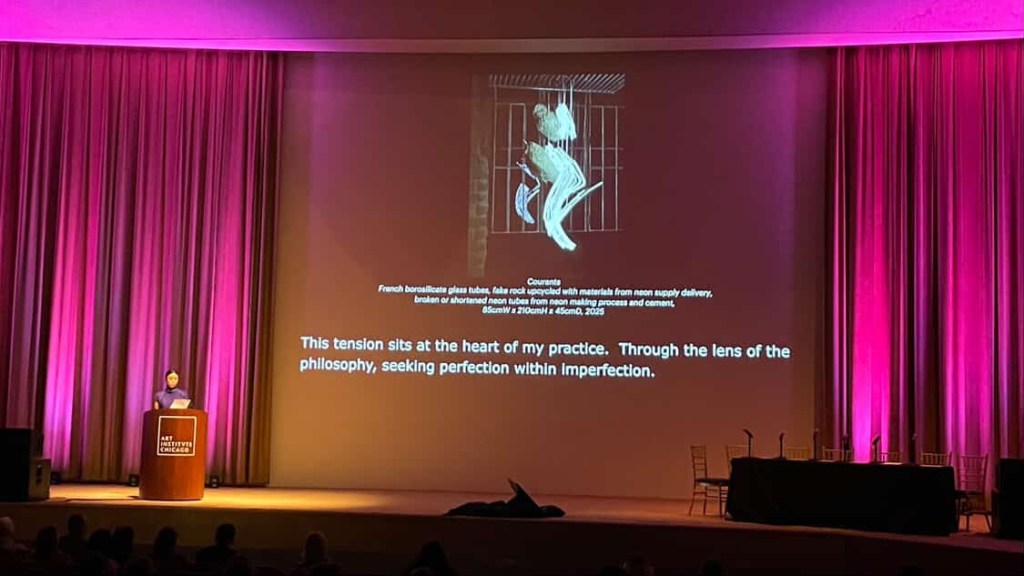

During my talk at the Art Institute of Chicago symposium — “The Persistent Glow: The Conservation and Continuity of Neon Artworks“, I explored how language has shaped my neon journey — not just as a means of communication, but as a framework for my artistic practice.

I spoke about Courants, and how the evolution of Chinese language and calligraphy inspired the fluid gestures in the piece — especially through the expressive cursive script of the water radical.

I also shared how I collaborated with Master Huang Shun-Lo in Taiwan to recreate a specific orange hue for Lion Rock Legacy: Made by Hand, Lit by Heart, repairing broken tubes remotely using photo comparisons and messaging — a sort of long-distance colour-matching therapy. And with You Are My Petals of Strength, I described sourcing rare red-coloured tubes from Japan with the help of my mentor, Mayuu-san.

In Light as Air and Courants, I also discussed how I obsessively source cables, stands, and materials across borders.

Sometimes, neon-making is just extreme shopping in multiple languages and time zones.

During the Q&A, (Mark?) from the audience asked:

“As a creator, how can you help conservators preserve your work?”

It caught me slightly off guard — I admitted my excessive shopping habits, buying out discontinued supplies while I can. I was tempted to say “we could 3D print them” — but for things like GTO cables, that’s just not realistic. Instead, I suggested that maybe artists should start providing extra materials when delivering a piece — spare tubes, cables, stands — things that could support future conservation efforts.

In the second part of the symposium and panel discussion that followed, the conservators shared specific existing strategies when delivering the neon works:

- Providing replacement neons

- Including sample tubes to preserve the original colour reference

- Sharing installation components like zip ties, neon stands, and GTO cables

(All of which, as Meryl rightly pointed out, should be properly valued and charged — not just thrown in for free.)

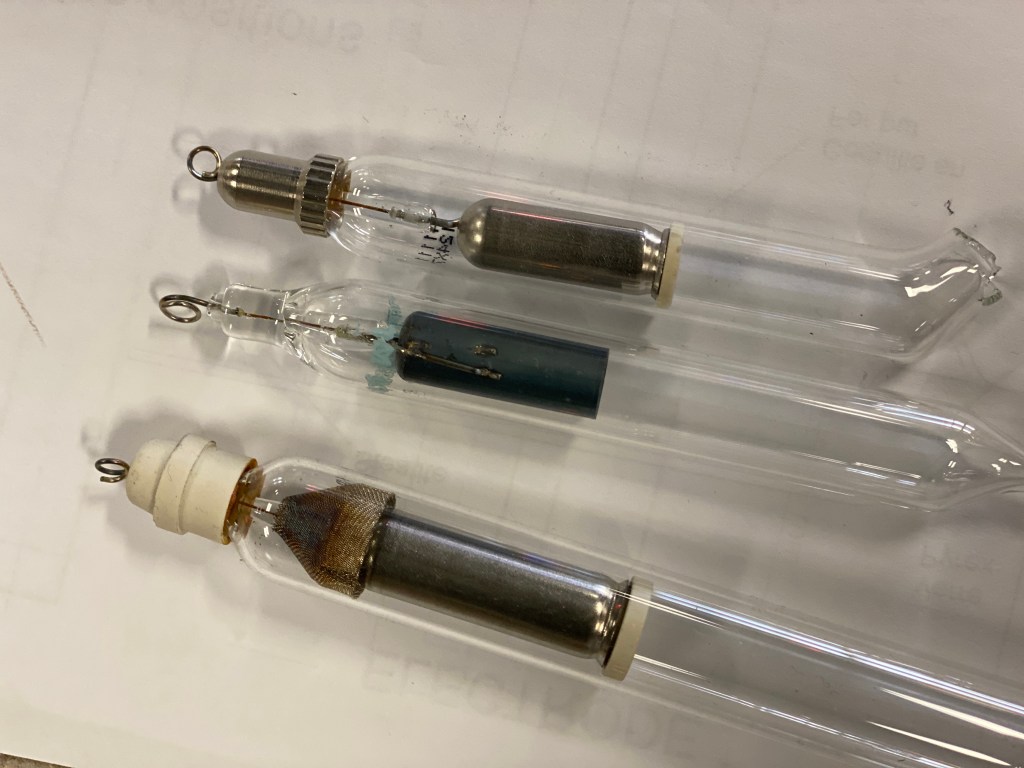

During the study day the next day, we examined the collected neon pieces at the museum. One fascinating example: an old white neon, its replacement, and a sample tube — which the latter two were supposedly made from the same batch of white glass.

Middle: Replacement neon

Bottom: Sample tube

With our bare eyes, the replacement looked like 3500K, while the sample appeared closer to 6500K.

The old neon was quite obvious that it was broken and there were new weldings on both ends. The interesting part for me personally was the replacement neon and the sample tube.

In Light as Air and Courants, I have used white neon tubes from Technolux and Glosertube respectively, ranging from 8mm to 20mm in diameter, with colour temperatures ranging from 3500K to 8300K. (Yes, the whites in these 2 works have variations.) I’ve come to understand that even within the same white spectrum (e.g. 3500K), the warmth of the colour can vary depending on the diameter of the tube. For example, an 8mm tube will appear brighter than a 10mm one.

What was astonishing, though, was that when the replacement neon was lit, it appeared to be around 3500K — whereas the sample tube looked closer to 6500K.

This raised a lot of questions, and the discussion quickly turned to why the replacement neon varied so much in appearance compared to the sample tube. It’s unclear how long the replacement tube had been on display, but there’s a strong possibility it was lit continuously during the entire exhibition period — even when the museum was closed.

I found it fascinating to listen to the conversation among Tom Wartman, Meryl Pataky, Tommy Gustafasschliöld, and Kacie Lees, as they explored different possibilities: whether the glass was lead-based, whether there might be a tiny invisible crack, or if air had seeped in over time, etc.

Eventually, Taylor used a UV light to show that the phosphors were the same — verifying the importance of keeping sample tubes for accurate conservation down the line.

And as to why the colour of the replacement neon is so different to the sample tube still remains a mystery. Maybe what Taylor said during the session is something we should all keep in mind:

Just because we haven’t found an explanation for something doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. Sometimes, the unknown is simply what hasn’t yet been understood

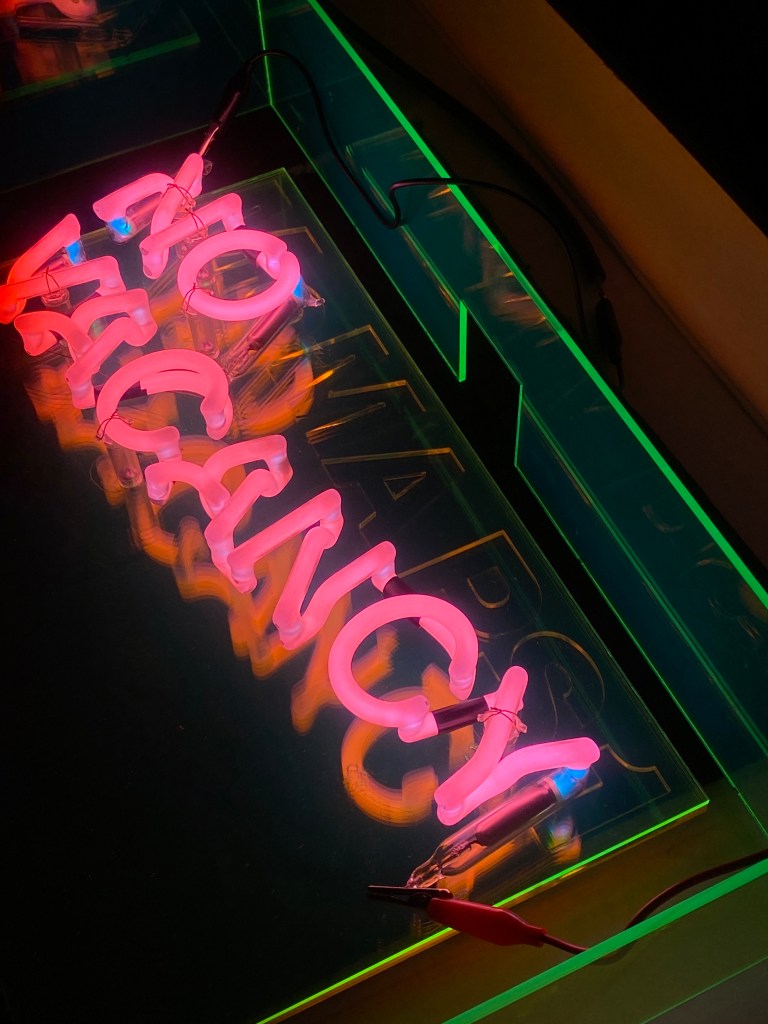

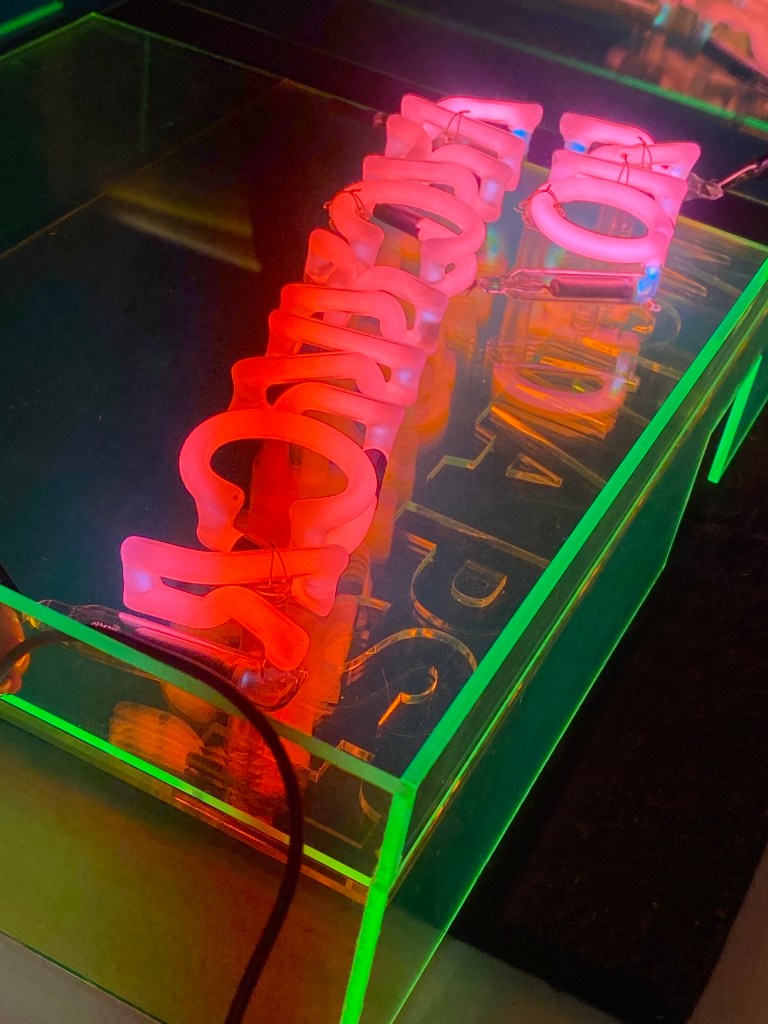

Next, we examined this French bent looking pink neon. I immediately recognised the electrodes and bending style — it reminded me of what I had seen at Lycée Dorian in Paris, and of an old neon sign in Alexis’s studio during my internship with him.

At first, there was debate about where it came from. Tommy guessed Turkey, citing the heavy mercury use. My guess was either France or Germany — leaning toward Germany because it used electrical tape rather than block-out paint for light block-outs. The bending style also reminded me of a similar sign I saw in the Netherlands. My Dutch teacher, Remy, told me at the time it was likely German-made.

There was also discussion about whether the tube was made from soft glass or borosilicate. Personally, I only know how to do that type of bend with borosilicate — and since it’s thicker and tolerates more heat and reheating, it’s wild for me to think anyone would attempt it with soft glass.

Below is a little example of how I made Lion Rock Legacy: Made by Hand, Lit by Heart with the French retour carré. I used the same single torch as seen in the video to bend the “HK heart” section — and only a hand torch for the welds. (Unfortunately, I didn’t record that part — I would have, had I known how valuable it might become later for conservation)

Personally, beyond the aesthetic reasons, I like using the French bent (retour carré) because — as someone still gaining confidence in bending — it gives me more room to fix errors and rework pieces. Many benders in Paris now use U-bends, like in most parts of the world, the retour carré is still around and recognisable in old and new signs.

After all this, my biggest takeaway as a creator is this:

Maybe I should start documenting my process more thoroughly — not just photos and videos for social media, but clear records of how each piece is made, especially bends and materials.

Sometimes I avoid filming difficult steps because it stresses me out — and honestly, the more stressed I am, the more likely I’ll break the tube! But in hindsight, having this information helps me (and others) identify how the piece was made, even years later.

This study session has made me realise how helpful even a small bit of process documentation could be for future preservation.

Before the official video of my symposium is live, you may find the script of my speech below:

你好, はじめまして. Je m’appelle Chankalun — 你也可以叫我 Karen.

Ik ben een neon artist from Hong Kong, now based in Paris.

My artistic practice is grounded in language, culture, and the philosophy of “seeking perfection within imperfection.”

That mindset guided me through The Neon Girl — a journey I began in 2021 to trace the art of neon-making around the world.

When I first began the project, I honestly had no idea how far it would take me, or if I’d even be able to keep up with the language, the tools, and the fire.

But I was curious. And maybe that was enough to start.

I travelled through six countries and regions, researching and learning from eight masters, craftsmen and artists.

And along the way, the languages I spoke — like Cantonese in Hong Kong, Japanese in Tokyo, Mandarin in Taiwan, English in New York, Paris, and the Netherlands.

They weren’t just communication tools, they were passports into completely different neon cultures. Each language opened a door into a different world of neon:

At Alkmaar in the Netherlands, I started with wide eyes and no clue what I was doing.

In Hong Kong, I rediscovered a craft that had always been quietly present in my life.

In Paris, I found both heritage and a healthy dose of bureaucracy.

In New York, there was passion, confidence and improvisation.

In Tokyo, I was drawn to delicate precision and quiet reverence.

And at Hsin-chu in Taiwan, I discovered experimentation, innovation – and extreme humidity.

This journey wasn’t just about bending glass.

It was about how knowledge is passed down, protected, and sometimes even hidden.

In most places I visited, neon is taught through informal apprenticeships. I met technicians who had only learned fragments of the process. Some of them had to cross borders just to fill in the gaps — learning bending in one country, bombarding in another. I was incredibly lucky: every teacher I met was generous, open, and deeply passionate.

Whether I was speaking fluent English, rusty Mandarin, or clumsy Japanese, their willingness to share always came through.

I realised that the true language of neon is patience.

But when we could communicate — even just a little — I received more than the technical savoir-faire. I got stories, cultural context, and a shared sense of friendship and brotherhood.

In all my travels, France and the US were the only places where there is formal neon education — not just workshops or apprenticeships, but actual institutions where you can learn the technology and history behind it all.

In 2023, I enrolled at Lycée Dorian in Paris, the last remaining public high school in France that still teaches neon-making.

The tools, materials, and techniques used there were unlike anything I’d seen elsewhere. We even studied the global history of glass — something I didn’t expect in a high school, but enjoyed and loved. I also learned that the neon gas was discovered in the UK in 1898, and that the neon technology was first invented in France in 1910 by Georges Claude, which makes France a bit like the godfather of neon — with a lab coat.

Being immersed in Paris, and exposed to the world of beaux-arts, has made me reflect deeply on my own voice as an artist.

I began creating works that merged neon with Chinese calligraphy. In cursive script, raw emotion and vulnerability are embraced

— while neon, by contrast, demands precision with each gesture calculated. This tension sits at the heart of my practice, through the lens of the philosophy: “seeking perfection within imperfection.”

My installation Courants created during my time at POUSH in Paris is one example. It is a suspended neon sculpture that feels more like a stroke in the air than a solid object.

The piece began with a simple question:

How do I represent water — not just as an element, but as a reflection of how humans perceive the natural world?

That led me back to my own language.

In ancient Chinese, the character for “water” began as a pictogram — flowing lines representing movement. Over time, the character evolved through the Oracle bone script, then Seal script, then Clerical script and so on to the Regular scripts nowadays — but its original visual essence remained.

Today, it’s still present in many compound characters where the words are water-related, all share the same water radical, like “river,” “wave,” “sea,” “wash”.

In Courants, I worked with the cursive script form of that radical. I chose it for its expressive, emotional quality — its looseness, its rhythm, its refusal to be boxed in. That raw movement created an intentional tension with the scientific precision of French neon.

Around the same time, I started exploring what it means to bring French neon craftsmanship abroad — not just as material export, but as part of an evolving visual language.

In Lion Rock Legacy: Made by Hand, Lit by Heart, a piece commissioned by Kee Wah Bakery, where I created using borosilicate tubes in France, and then shipped them to Hong Kong for installation.

Most of the time, I find myself passive when it comes to colour — I can only work with what suppliers happen to have in stock. And not just locally, but in Italy, France, China, or the US.

What made that piece special wasn’t just the borosilicate tubes nor the French techniques, it was the colour.

I was chasing a specific soft orange glow.

I ended up using a yellow coloured glass tube, coated with green phosphor, and filled with neon gas. That combination gave the exact hue I wanted.

But — as every neon artist fears — some of the tubes broke during the installation. I was devastated — but also lucky to be able to turn to my Taiwanese master, Huang Shun-Lo, to help me to recreate the same colour. We collaborated entirely through photo comparisons and Facebook messaging. It was like long-distance colour-matching therapy — but we pulled it off. He did numerous tests and mixed phosphorus powder to create a similar hue.

I have actually worked with Master Huang before, during The Neon Girl project, for the work, Mother Nature.

Most of the neon tubes nowadays came powdered with phosphorus powder when you buy them. For Mother Nature, we did something uncommon: First, we used a thin tube to transfer some phosphor powder into the bent tubes, then we blew phosphor powder directly into them— and just like that. He said it would only work if there was enough humidity in the air. Now, being up in the mountains, Hsinchu in Taiwan is already a humid place. But the day before, he still brought out a humidifier, just to be sure the phosphor would stick properly. That was one of those moments where science meets superstition meets absolute dedication — and it worked.

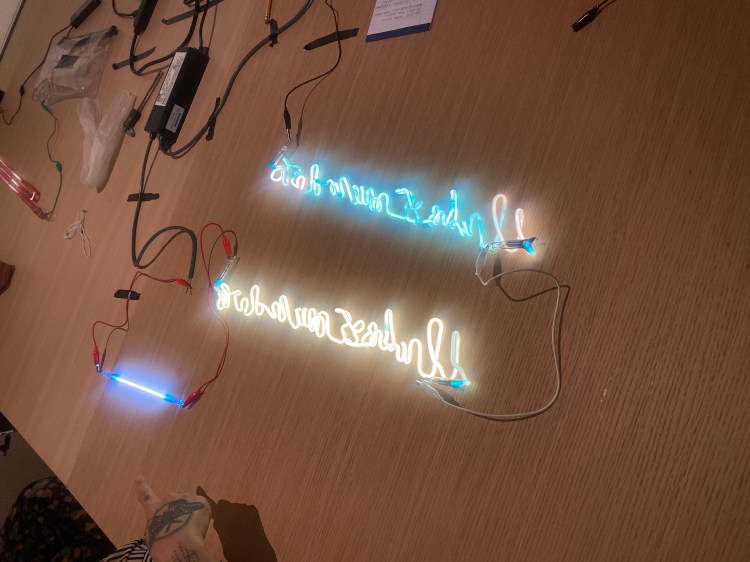

Another example of my active pursuit of colour is You Are My Petals of Strength, made for Love, Bonito — where I became obsessed with red. During my Tokyo research, I was drawn to the city’s spectrum of reds — from bright signal red to rich velvet hues. I later found out that the colour I loved came from an earlier stock of red-coloured glass filled with argon gas – a colour that can’t be perfectly replicated anymore.

Glass colours, especially those produced years ago, aren’t always available everywhere or at any time. Even when production still exists, the batches can vary by region or supplier — which makes the colour consistency across borders a real challenge.

My Japanese mentor, Mayuu-san, helped me source and ship the tubes to Hong Kong. I had to handpick each one of them from an almost-extinct stockpile just to ensure consistency.

Over time, I’ve started compiling lists of materials and suppliers across the globe. It’s not glamorous, but it’s the backbone of every artwork. I choose different neon stands or cables depending on the aesthetic and effect I’m aiming for each project. And I compare the cable thicknesses, electrode types, stand heights and etc. — often just over email or the occasional phone call.

In Light as Air, a monumental piece I made for La Prairie at Art Basel Hong Kong, I wanted the piece to appear as if it is floating mid-air

and suspended with as little visible structure as possible. Back then, I used 20mm diameter neon stands sourced through Master Huang in Taiwan — mostly because they were the only ones I could find at the time that fit the tube size and still looked elegant.

When I created Courants, I wanted to refine the floating effect even further. I needed neon stands that were ultra-short — so the neon would appear almost invisible, as if they were gently kissing the acrylic frame. I also wanted some of them to be taller, to create different layers for a sculptural effect. So I sourced the neon stands of different heights from Ablon Technologies, Sign-Tec UK, and Hyrite China — trying to balance cost, aesthetic and practicality like a supply chain acrobat.

And then — of course — there was the cable. I remembered seeing a stunning suspended installation by Cerith Wyn Evans at the Pompidou Metz in France, using a thin MATEL 5kV cable. I hunted it down eventually — only to find that it has been discontinued and out of stock. After many emails and dead ends, I finally sourced a similar cable through Hansen in Germany.

Sometimes, neon-making is just extreme shopping in multiple languages and time zones.

I’m a Hong Kong girl, so I guess this is one of my expertise 😉

Some of the materials I use simply don’t exist anymore — like those older red glass tubes that are no longer in production. Once this generation of craftspeople is gone, much of that tacit knowledge — not just of neon-making, but of how to source, adapt, and engineer the machines and materials that support it — like the cables, stands, transformers and even burners — may vanish with them too.

All these material deep-dives taught me something unexpected:

how fragile language can be in the world of conservation. Between technicians, conservators, and suppliers — translation errors are surprisingly common, especially with technical terms.

In my early days, I tried to translate “bombarding” — and somehow, it always became “explosion” in another language. That is not ideal, and definitely not what you want neon to sound like.

I’ve since learned the proper terms:

chargement du gaz in French, 入氣 in Cantonese, and 排気 in Japanese — all meaning the same process, but more gently as “charging or inserting or releasing the gas.”

And that leads me to think, maybe that’s why public myths about neon still persists:

“Will it explode?”

“Is the gas toxic?”

“Isn’t it dangerously hot?”

And I get it.

Over the years, I’ve met so many people — from collectors to electricians — who thought all those things were true. But once they saw how neon is really made, they were fascinated. Some even became neon practitioners. Others just never saw neon the same way again. Maybe what we call ‘material knowledge’ is also a kind of cultural translation.

I believe that with better education, clearer communication, and more artist-led storytelling, we can help people understand neon as what it truly is: a luminous, precise, poetic artisanal craft that deserves to be preserved, evolved, and celebrated. And since we’re all here because we care about preservation, I think we share the same mission — to protect what glows, and let it evolve.

And beyond its glow, I also ask myself:

Can language itself become a sculptural trace of history?

Through studying the evolution of Chinese calligraphy — and how it reflects the way humans perceive and record the world — I try to answer that question by reimagining it through the glowing lines of neon.

If language opened the doors to my journey, then maybe now, — through neon — it can help light the way forward for others too.