When Mila from L’AiR Arts invited me to spend three weeks in residence at Atelier 11 (Cité Falguière)—an artist-run site with 150 years of history and a long tradition of hosting international artists—I chose to approach the time as a research-led residency, alongside studio work.

During the first week, I was focused on reading around language and cognition—how humans learn, categorise, and transmit meaning—drawing on texts by Steven Mithen, Daniel L. Everett, and others. These readings became a way to sharpen the questions behind my work, rather than to “explain” it.

During my time at Atelier 11, I keep returning to the same question: how can we give form to forces we cannot see: air pressure, currents, underground movement, without reducing them into illustration? My approach has been Chinese calligraphy, especially cursive script: used not as decoration nor literal translation, but as a way to sculpt rhythm. Each brushstroke is a record of breath, hesitation, speed, and release. In that sense, it can stand in for the invisible.

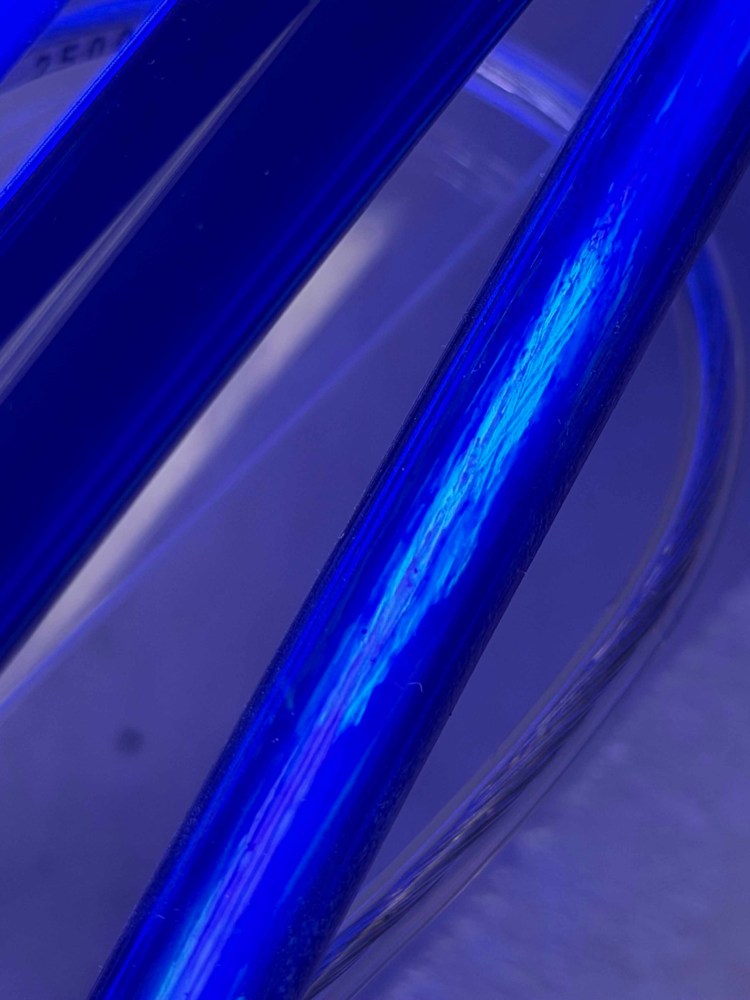

This is also where my long engagement with the philosophy of “seeking perfection within imperfection” becomes concrete. In Chinese cursive calligraphy, a “mistake” is not always a failure – it can be evidence of emotion, vulnerability, or the limits of the body. Neon is the opposite.

To bend glass, I rely on planning, timing, measured physical gestures, and precision. One second too long on the flame and the tube collapses. The work lives within that tension: an expressive language that can accept instability, and a material that does not.

Alongside the studio work, reading more broadly around the neuroscience of language learning has sharpened something I didn’t fully address before: how language as a way of passing down technique, and about technique as a condition of survival tied through tools-making.

That line of thought leads quickly to the earliest technologies that reshaped human life – and fire is one of the most fundamental. It allowed humans to transform matter, protect themselves, and gather together. It changed how we ate, how we moved, how we stayed alive, and by extension, how we evolved orally. It is also same element I rely on daily to make neon. The flame in the studio carries a longer history than we usually acknowledge.

This has led me to question whether my practice is quietly about power. Not power as domination, but power as an invisible force that shapes behaviour: currents in a river, heat in the glass, the words we inherit and repeat, and the language that lets us coordinate and act together. The story of the Tower of Babel sits in the background here: a myth in which shared speech enables collective action, and the fragmentation of language breaks that strength. Natural forces, fire, and language all operate in similar ways: intangible, but decisive.

Another idea that has become central for me is “trace.”

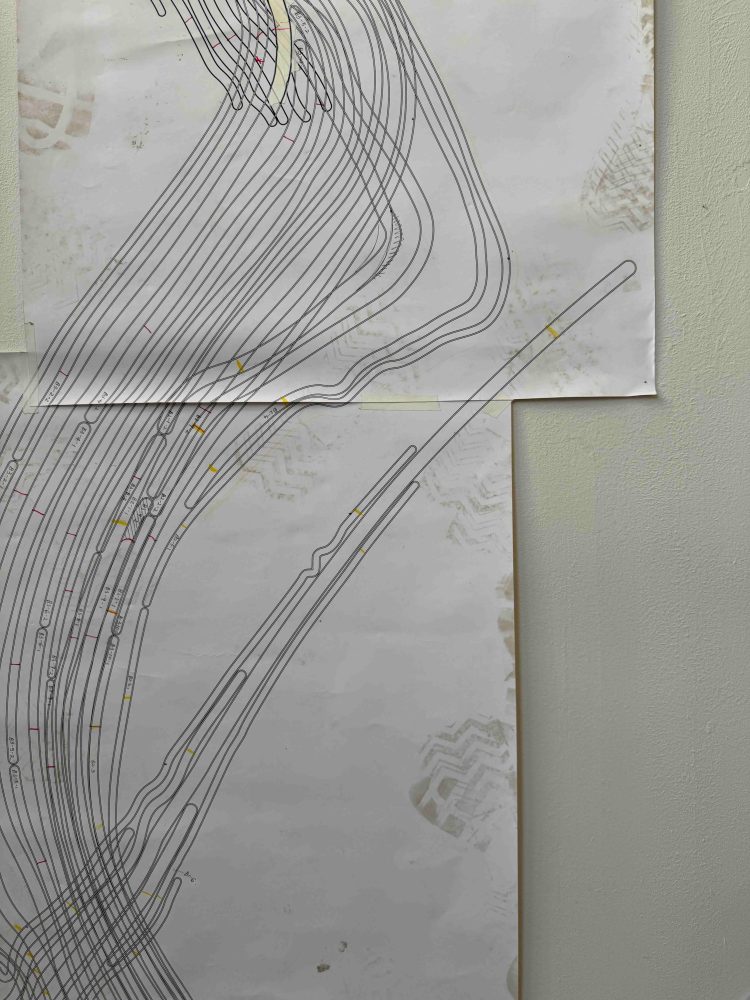

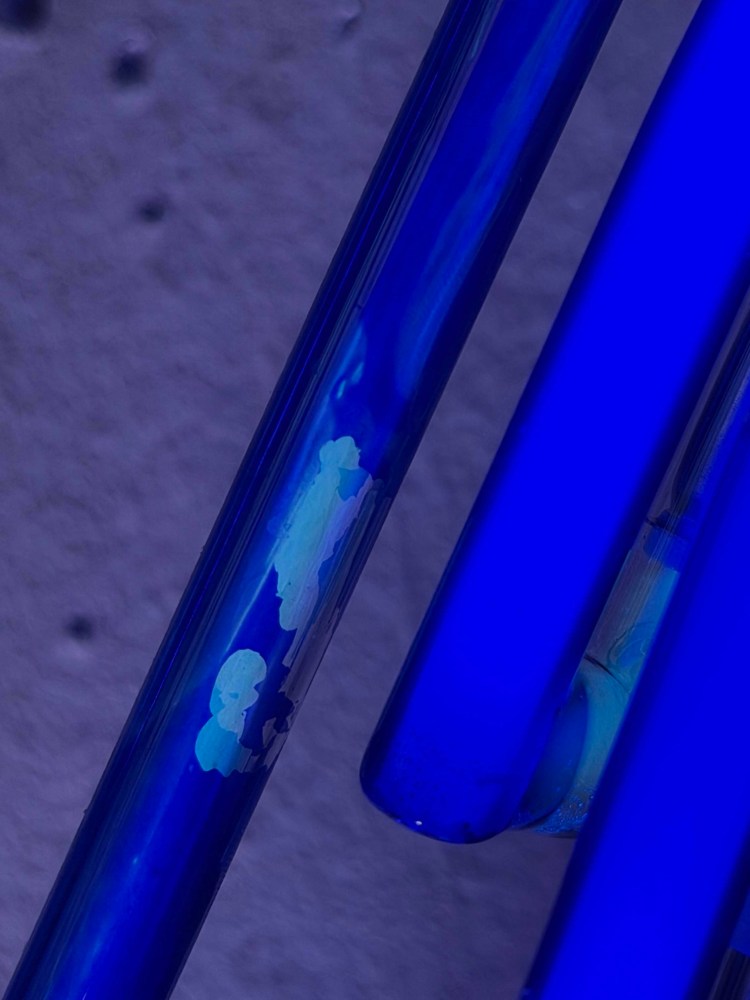

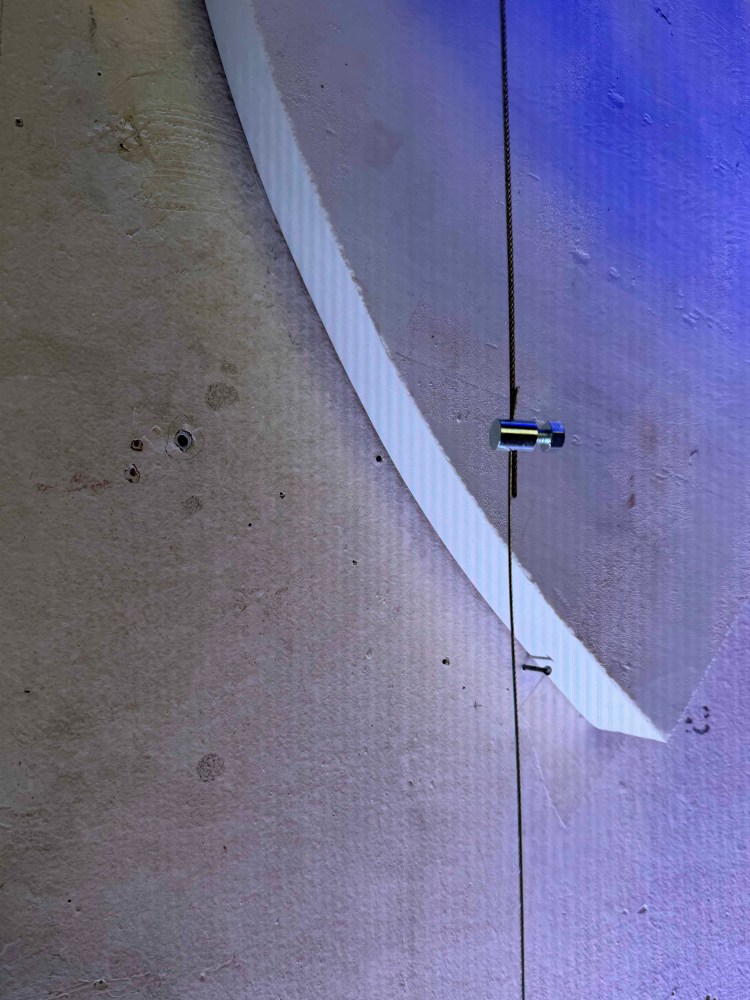

Each installation is a record of its own making. Every hand-bent tube retains the memory of the flame. Hand-painted surfaces hold brush marks, fingerprints, and dust, etc. Packaging bears the evidence of transport: chipped areas, broken segments, repairs… Even the hardware accumulates history. Terre, for example, has already been installed in three different places; it still carries elements from its first version at Braziers Park in Oxford, alongside revisions that only exist because the work has travelled.

I’m beginning to see a practical parallel with learning in my practice: repetition strengthens pathways; interruption forces new ones. You don’t return to the same state; you adapt. That’s true for the brain, and it’s true for an artwork that is installed, dismantled, repaired, and shown again. For Terre at Atelier 11, I can already anticipate recurring traces: old and new wiring crossing, sections renewed while others remain “accented” by time, and broken tubes replaced with newly bent white glass. I don’t treat the replacement as a hidden repair; the shift in colour stays visible, like new information layered onto an older structure. Over time, the work could drift toward a different state, perhaps even toward an almost fully white piece, not because it becomes “better,” but because it survives through repair.

That’s also how I want to think about language at Atelier 11: not as something that becomes perfect, but as something that keeps adjusting and adapting, layering new forms onto old ones, staying just coherent enough to carry us forward.

Selected readings:

Junaid Mubeen, Mathematical Intelligence;

Steven Mithen, The Language Puzzle;

Ilario Sinigaglia, Language: A Different Use of the Brain;

Daniel L. Everett, Language: The Cultural Tool.

Featured photo credit: Tamara Benarroch